To the passer-by ‘Bryn Gwyn’ appears as a ‘lovely old cottage’. They are unaware that the traditional lime washed house they are looking at was at the centre of lead mining in the Alyn valley during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The house dates back to 1756 was built for the ‘Captain’ or ‘Master’ of the mine. It is described by CADW as being the best preserved of a small group of buildings that includes an engine house and blacksmiths/joiner’s workshop associated with the Llyn-y-Pandû and/or Pen-y-Fron mines. The traditional lime washed render over stone rubble, slate roof and a central door that is flanked by 16 pane sash windows are characteristic features of a house of that time. An extension was added to the rear in the early 19th century and there are two brick vaulted cold stores and other stone out buildings within the grounds.

From the middle of the eighteenth century onwards for almost a hundred years, the Llyn-y-Pandû and Pen-y-Fron mines were the centre of entrepreneurial endeavour. Miners and owners alike found themselves in a constant battle against fluctuating underground water levels to mine the rich veins of blue and white lead ore that lay beneath the ground. It was a precarious operation and despite the efforts of several mine owners including Richard Ingleby and John Wilkinson investing in engines to pump the water out, the mines were often at a standstill.

By the 1780s Richard Ingleby, the son of Thomas Ingleby who had interests the lead mines on Halkyn Mountain and owned the Gadlys smelting works at Bagillt held the leases for both the Llyn-y-Pandu and Pen-y-Fron mines. However the ongoing difficulties he experienced at the former forced him to call upon John Wilkinson Esq. from Bersham who took over the mine. By 1791 he had four ‘Boulton and Watt’ type engines working to clear the water from the levels.

Such was the interest in these mines that in 1798 the Rev. Richard Warner set out to see the Llyn-y-Pandu mine for himself and in his book A Second Walk through Wales describes how

‘Another hour brought us to the object of our day’s ramble, Llyn-y- Pandu mine, the most considerable lead mining speculation in England. The scenery of this place is wonderfully wild and romantic; a deep valley rude and rocky, shut in by abrupt banks, clothed with the darkest shade of wood’

Meanwhile by the 1790s at the Pen-y-Fron mine, despite incurring heavy losses initially and being hampered by water so much so that the lower levels could only be worked during long spells of dry weather, Richard Ingleby had made his fortune.

Walter Davies (Gwallter Mechain) in 1810 whilst compiling his ‘General View of Agriculture’ describes how at the Pen-y-Fron mine

‘with no other engines than pickaxes, buckets, windlasses and wheelbarrows … quarried out from 30 to 50 and sometimes a100tons of ore a week’

It has been estimated that the majority of the 27,500 tons of ore estimated to have been raised before 1820 came from the Pen-y-Fron mine whilst John Wilkinson oversaw almost 20,000 tons of ore being raised form the Llyn-y- Pandu mine. The heyday of both mines was short lived and by 1830 both the Llyn-y-Pandu and Pen-y-Fron mines had closed.

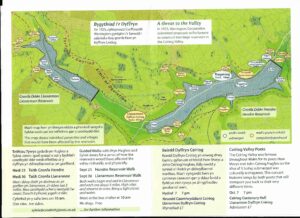

The Engine House The Joiner’s Shop

Blog articles will only appear in the language they are provided in by the author.

Yn yr iaith y’u hysgrifennwyd gan yr awdur yn unig y bydd yr erthyglau blog yn ymddangos.